Recently, Justice Anthony Kennedy, the longest serving justice on the Supreme Court, having been appointed by President Reagan in 1988 officially announced his retirement. Justice Kennedy was considered the Supreme Court swing vote on many of the Court’s  blockbuster cases from abortion to gay rights to affirmative action and the Second Amendment. The announcement of his retirement has energized constitutionalists as the president now has an opportunity to appoint a consistent constitutionalist voice to serve on the high court.

blockbuster cases from abortion to gay rights to affirmative action and the Second Amendment. The announcement of his retirement has energized constitutionalists as the president now has an opportunity to appoint a consistent constitutionalist voice to serve on the high court.

The president has announced he will pick from a list of 25 to replace Kennedy and the announcement will take place on July 9. With that being said, here are my thoughts on worthy finalists for the seat. I have named my 3 top candidates and a dark horse candidate that will likely not be named this time around, but if another opening emerges would be a strong choice in the future.

Top Choice- Judge Amy Barrett of the Seventh Circuit

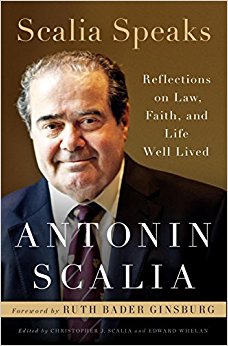

Judge Barrett recently assumed her position on the Seventh Circuit after serving as a very well respected academic and scholar at Notre Dame Law School for several years. She is a graduate of Notre Dame Law School and clerked for Judge Laurence Silberman of the D.C. Circuit and the late great Justice Antonin Scalia at the U.S. Supreme Court. She has seven children and is a very devout Catholic.

Judge Barrett presents many advantages, she is a renowned legal scholar with first-hand experience working with the top legal minds in the nation. She also has braved through difficult confirmation hearings for her Seventh Circuit appointment and will not shy away from another challenging process. Some may remember these hearings for the attacks she endured for being a devout Catholic in the legal community.

In terms of the law, her legal philosophy is rooted in constitutionalism and originalism as evidenced in her writings. She has written:

“The Constitution’s original public meaning is important not because adhering to it limits judicial discretion, but because it is the law. . .the measure of a court, then is fidelity to the original public meaning, which serves as a constraint upon judicial decisionmaking. A faithful judge resists the temptation to conflate the meaning of the Constitution with the judge’s own political preference; judges who give into the temptation exceed the limits of their power by holding a statue unconstitutional when it is not.”[1]

Furthermore, she is not overly bound by the philosophy of stare decisis which promotes a strong adherence to prior court decisions even if they have questionable grounds. One who has an overreliance on stare decisis follows prior decisions closely and plays extra attention to how long they have been law and is often reluctant to issue a sweeping decision to disturb precedent. Judge Barrett has recognized in her writings that judges should not be over relying on stare decisis, it is merely a factor. If decisions were wrong the day they were decided they are still wrong today. The Court should not be relying on stare decisis as a prevailing factor, the Court first and foremost should be adhering to the Constitution.

Some may point to her judicial inexperience as a negative, however, that same sentiment was once echoed for another judge, Clarence Thomas, who has become of the top judges of the modern era.

Overall, I believe Amy Barrett should be the top choice for the Supreme Court vacancy. Her intellect and proven accomplishments as a respected legal mind will be a great asset to the court for years to come.

Senator Mike Lee

U.S. Senator Mike Lee is another notable name that has drawn intrigue to fill the vacant Supreme Court seat. Mike Lee represents the Utah in the senate and has a proven conservative record. He graduated from Brigham Young Law School and clerked for current U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito when Justice Alito served on the Third Circuit. Before becoming a senator he specialized in appellate and Supreme Court litigation. As a senator, he serves on the judiciary committee.

Judge Thomas Hardiman of the Third Circuit

The runner up to Justice Gorsuch for Justice Scalia’s seat, Judge Hardiman currently sits on the Third Circuit. Judge Hardiman is a graduate of Notre Dame and Georgetown Law School. His judicial record indicates strong support for the Second Amendment and he  also joined an opinion vacating the conviction of an anti-abortion protestor who was peacefully protesting. He also possesses a strong judicial record recognizing religious freedom interests. Having joined the Third Circuit at age 41, he has many years of federal judicial experience and would be a strong fit for the court.

also joined an opinion vacating the conviction of an anti-abortion protestor who was peacefully protesting. He also possesses a strong judicial record recognizing religious freedom interests. Having joined the Third Circuit at age 41, he has many years of federal judicial experience and would be a strong fit for the court.

I also should note, having personally met him he was a very genuine and soft-spoken individual. He exerts a humbleness about him that should garner a great deal of respect from his peers.

Dark Horse: Judge Patrick Wyrick of Oklahoma Supreme Court and U.S. District Court Nominee

Judge Wyrick is only 37 years old and his name has been rising in conservative legal circles for his work as an Oklahoma Supreme Court Judge and former solicitor general of Oklahoma. While his nomination is unlikely with his relative youth at this point, expect his name to gain steam if another vacancy opens. He has been nominated to serve on the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma and is awaiting a vote before the senate. It is clear that his career is being fast-tracked to one day reach the circuit level or perhaps the Supreme Court.

Some of Judge Wyrick’s significant experiences include representing Oklahoma in challenging the Affordable Care Act and representing the interests of the state in a notable death penalty case.

[1] Barrett, Amy Coney, “Countering the Majoritarian Difficulty” (2017). Constitutional Commentary. 4

moving to me. Today’s post will focus on the speech “The Vocation of a Judge” that the late justice gave in Peru in 2007. It is a timeless lesson and should help shape our perspective on how to view judges as guardians of the law.

moving to me. Today’s post will focus on the speech “The Vocation of a Judge” that the late justice gave in Peru in 2007. It is a timeless lesson and should help shape our perspective on how to view judges as guardians of the law. considering the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973, the question of its legal prowess could have been maintained in the state context through state law and amendments to state constitutions through referendums if necessary. One may contemplate the degree of personal biases in both these decisions and question if the reasoning reflected that of good judging.

considering the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973, the question of its legal prowess could have been maintained in the state context through state law and amendments to state constitutions through referendums if necessary. One may contemplate the degree of personal biases in both these decisions and question if the reasoning reflected that of good judging.